Baby bear and label

I slept with my blanket, Label, and teddy bear, Baby Bear, every night until the summer I was 24 years old, when I lost them in a hostel in Vienna. I checked in early and immediately made my bed and put my bear and blanket on the freshly made bed. When I came back after lunch the sheets had been stripped and the bear and blanket were gone with them. My comfort objects were permanently lost in the bowels of an industrial linen service; I imagine they ended up in a landfill somewhere. Just over a month later my mother died.

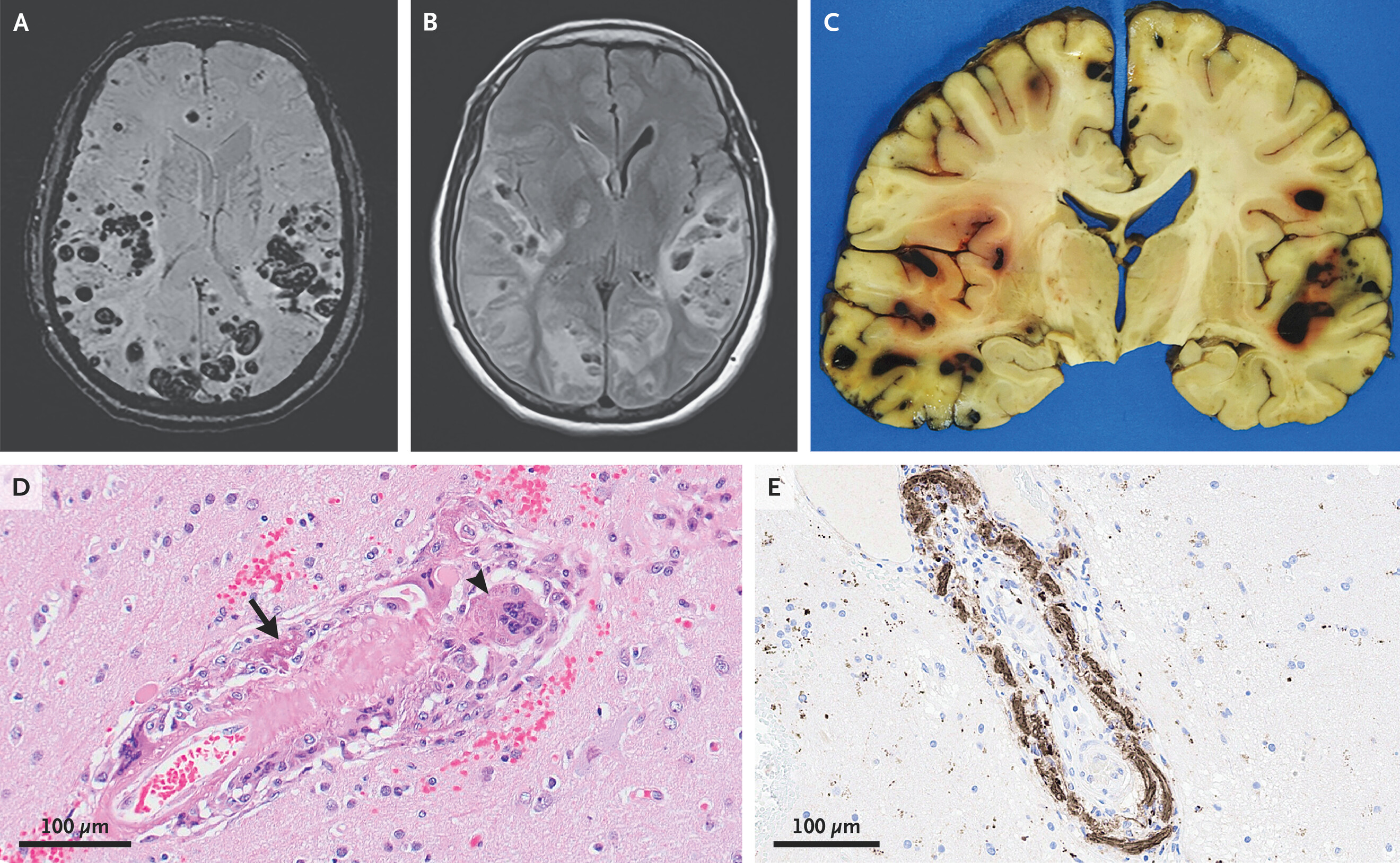

She was killed as a freak result of a drug trial. You know when the medication has all that fine-print text about the terrible things that could possibly happen under certain unusual circumstances? They know exactly how unlikely those things are and exactly how bad they can be because they each happened to enough people to establish a statically meaningful correlation. My mother was one of those people that one of those things happened to, and now we know that you probably shouldn’t take Lecanemab if you’ve got the APOE ε4 allele. The article reporting my mother’s death is called “Multiple Cerebral Hemorrhages in a Patient Receiving Lecanemab and Treated with t-PA for Stroke”, and it’s where the photos of her brain at the top of this entry come from. Hers and similar cases caused the FDA to put a boxed warning, the strongest warning the agency, about the interaction between amyloid related imaging abnormalities, APOE ɛ4, and Lecanemab on the label of the medication when they approved it.

There’s a symmetry to the meaningless brutality of these deaths (or “deaths”, in the case of Baby Bear and Label): a decisiveness, an efficiency, a disregard for the material being swept away. We live in a violent world, one where human life is cheap and easily thrown away to grease the wheels of a grander project, or a project we perceive to be grander than the life we’re tossing out. Life is cheap. What did my mother accomplish in her life? What was her contribution? The FDA said: “fatal cerebral hemorrhage has occurred in a patient taking an anti-amyloid monoclonal antibody in the setting of focal neurologic symptoms of ARIA and the use of a thrombolytic agent.” That’s my mother, I’m pretty sure. I can’t even identify her in the anonymous language: “fatal events of intracerebral hemorrhage in patients taking LEQEMBI [generic name of Lecanemab] have been observed.” I personally observed one such event when I felt the change in my mother’s body from living to dead three years ago today, almost to the minute. My step-father and I stood by her in the hour it took her to die of asphyxiation after we removed the breathing tube (she actually died of failing to clear her throat). She gasped for breath like a fish and her flesh became pallid and yellow. I caressed her hand and hugged her. I sang to her. I cried. In the very last moment when her heart stopped, I hugged her; the visceral wrongness before and beyond disgust of touching the body that was once my mother repelled me, and I leapt back. There was nothing satisfyingly clean about it, no immediate disappearance; she died the same way everyone does: one breath, one heartbeat at a time.

But all that’s wrapped up in the neat drug packaging (“LEQEMBI (lecanemab-irmb) injection is a sterile, preservative-free, clear to opalescent, and colorless to pale yellow solution […] Each glass vial is closed with a stopper and flip cap.”) with an ugly box on the information leaflet that’s there because of my mother and a few others with stories like hers. Those neat little “carton[s] of 1 single-dose vial” don’t give me the same comfort as my fuzzy bear and soft blanket did, and I miss them very badly right now. I’d like to sink my face into their softness and smell the must and warmth they’d gathered since being in bed with me from infancy. I’d like to smell my mother again: not the hospital-sanitary smell of her at the end, but the warm clean smell of her when she was still alive. But they’ll never be physically present to me; they only half-exist anymore, ghostly, as fragments and memories.

My mother always said I took a piece of her with me when I was born, and that I’d always have her with me. It’s an imperfect consolation, but some consolation is better than none. After I’d checked out of the hostel and gave up on Baby Bear and Label, I was by the Danube and saw a stuffed bear floating down the river. I crossed the bridge and went down to the side of the water and caught the bear as it floated by. It isn’t Baby Bear, but it’s like a trophy I’ve been granted, an abstract representation of what Baby Bear was like: it even has a little collar of the same blue, white, and red as Label was. It’s still in a box in Chicago. And, of course, there’s Xerxes, who was my real comfort animal the years after my mom died. He’s also safe and well in Chicago. Someday they’ll be gone too, as will I, as will you. But right now the piece of me that’s my mother is warm in my heart, and I’ve learned to sleep with my arms empty of comfort objects.